As was the case at Langley Air Force Base in Virginia last December, foreign adversaries are flying drones over sensitive U.S. military bases and into military training areas to spy on U.S. forces. China is the chief culprit here. Beijing’s intent was to learn and anticipate how U.S. forces would fight and how, in turn, those forces might more easily be defeated in war.

Considering the growing risk of a U.S. war with China over the Philippines or Taiwan and Russia’s continued threat to NATO, it is intolerable that our enemies are so easily penetrating our airspace with effective impunity.

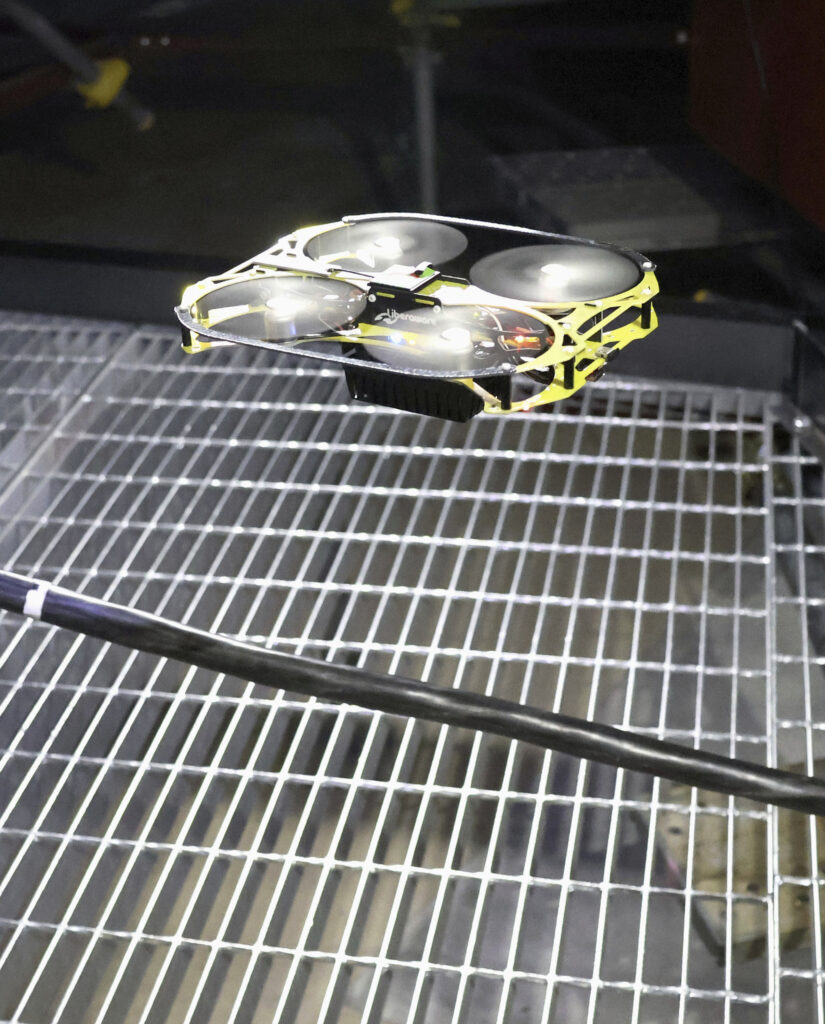

The value that an adversary might find in drone-based spying is significant and varied. Drones allow a spy to operate with secrecy and speed, deploying a small aerial vehicle out the back of an otherwise nondescript civilian car, flying the drone over a military base, and recording sites or activities of interest before quickly recovering the drone and driving off into the night. This method of espionage is affordable, deniable, and repeatable.

However, what if the drone operator decides to adopt the Ukraine war textbook of drone innovation? What if they then attach an explosive device to the drone? What was one minute a hobbyist toy has now become a kamikaze killer. Even if one kamikaze drone couldn’t kill that many people, it could cause damage to a priceless military asset such as an F-22 fighter jet. This is no small concern. Langley AFB is home to two F-22 squadrons.

The F-22 is the finest air superiority fighter jet in the world and would be of critical value in a war against China. Unfortunately, due to former defense secretary Robert Gates’s foolish decision to cancel the program, the United States has only 110-140 F-22s available for combat today. The loss of even one jet due to a surprise drone attack would be a big deal. What if a dozen drones were launched in a simultaneous swarm attack on six F-22s as they sat waiting unguarded on the tarmac? What if a dozen such attacks simultaneously occurred at bases from Alaska to Hawaii to Virginia?

The nation must take action.

One key focus must center on improving the military and government’s means of disrupting threatening drone activity. Federal Aviation Administration regulations currently make it illegal for anyone in the U.S. to shoot down a drone, even if that drone is over their property. This policy in itself is debatable, as an obvious balance must be struck between the facilitation of commercial drone use, public safety, property rights, and privacy rights.

Whatever balance has been struck by lawmakers on the civilian side, the balance shifts dramatically when the land in question is vital to national security. Current regulations forbid military personnel from using force to take down an intruding drone unless they perceive an imminent threat. These restrictions are designed to mitigate the risk to innocent civilian air traffic such as helicopters, planes, balloons, and commercial/hobbyist drones, which often saturate urban areas. Many military bases are close to civilian population centers.

The problem is that base commanders and officers of the watch need to know that their decision to order an apparently hostile drone shot down is more likely to meet praise from senior officers and not a board of review. Perversely, federal law is currently incentivizing the U.S. military to allow the U.S.’s enemies to spy upon it. What’s needed are clearer authorities to allow decisive action in the event an unidentified drone is assessed to be conducting threatening activity.

The threatening activity should not have to be a possible Kamikaze attack. If a drone is recording the location of where F-22s fuel, where their armaments and ground crews are located, that drone is enabling future military action against the U.S.

Considering that many military bases operate in proximity to civilian interests, it is important that any new rules be proportionate and tethered to accountability. Absent imminent threat, it should be the responsibility of the officer in charge to decide whether to order the use of force, not a private standing post. Considering the variances of weather and visibility alongside the variances of drone sizes, appearances, and speeds, there is a risk that non-hostile drones or aircraft operating outside of a military base might accidentally be fired upon in some scenarios. That’s why the military also needs better detection technology, anti-drone defenses, and video surveillance equipment.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Still, the status quo is plainly incompatible with national security. It is unacceptable that military personnel feel hamstrung in their ability to protect themselves and their assets against aerial threats.

Congress should take action to establish more robust defensive authorities in kind. If not, China will keep eating our lunch.